Brodie Helmet

At the outbreak of the First World War, soldiers went into battle with non-metal headgear. This differed depending on where they were stationed. Head injuries from shrapnel and debris increased, and the need arose for a stronger and more resilient helmet for soldiers on the front line.

At the outbreak of the First World War, soldiers went into battle with non-metal headgear. This differed depending on where they were stationed. Head injuries from shrapnel and debris increased, and the need arose for a stronger and more resilient helmet for soldiers on the front line.

In September 1915 a design patented by John Brodie was selected as the British Army’s standard head protection. The design meant the helmet could be cut from a single sheet of steel, and then pressed to form a ‘soup bowl’ shape. This made the helmet stronger, and easier to produce. The design featured a brim 5cm wide, which protected the head and shoulders from above. It was made of ‘Hadfield steel’, which could withstand the impact of some shrapnel. Unfortunately, the design lacked protection to a soldier’s neck and lower head, and also reflected light. The helmet was later modified to a light green, and covered with sawdust and cork, giving it a dull and non-reflective surface.

The first one million Brodie helmets were distributed in the summer of 1916. It was the first helmet given to all serving soldiers in the British and Commonwealth armies, regardless of rank.

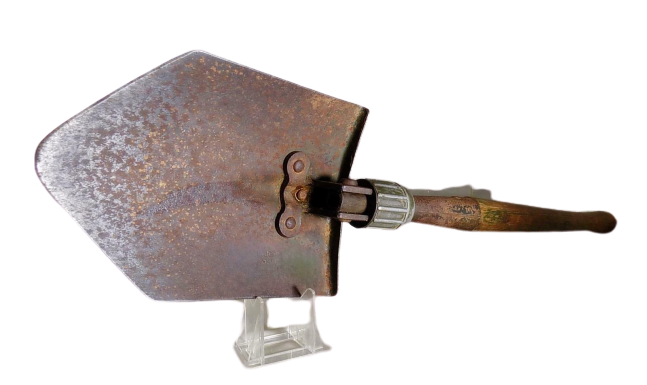

We have a 1945 US Army Entrenching Tool in our History of Medicine Collection.

We have a 1945 US Army Entrenching Tool in our History of Medicine Collection.  We have World War One shrapnel in our History of Medicine Collection.

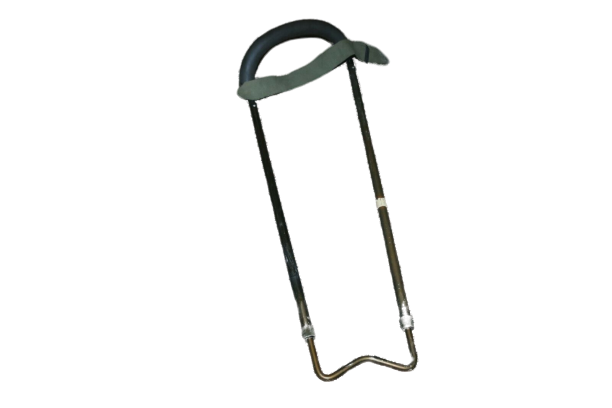

We have World War One shrapnel in our History of Medicine Collection. We have a World War Two Telescoping Thomas Splint in our History of Medicine Collection.

We have a World War Two Telescoping Thomas Splint in our History of Medicine Collection.  We have a portable blood transfusion kit in our History of Medicine Collection.

We have a portable blood transfusion kit in our History of Medicine Collection.